The unwritten contract underpinning the society and economy of New Zealand today has become perverted. Contracts are supposed to describe two-way entitlements and obligations on all parties. However, being increasingly seen as a one-way relationship has caused the contract to become perverted.

Property (and taxpayer) rights are now seen as paramount in today’s contract. This is accompanied by the narrative of welfare beneficiaries being a burden on the taxpayer. That is, taxpayers and property owners have rights, but others don’t. Others have obligations, but taxpayers and property owners don’t1. This is just one example of how the social contract has been perverted in today’s world.

It is beyond time to correct this perversion. A clearly articulated social contract that not only reinforces the rights and responsibilities of all parties, but also their obligations and responsibilities, is required. That will then enable a clearer identification of which parties are – and which are not – holding up their side of the bargain.

Is the social contract still relevant?

The relevance of the social contract was implied, surprisingly, by the UK Financial Times (FT) editorial on 04 April 2020. The editorial was headed Virus lays bare the frailty of the social contract.

When the FT acknowledged the existence of a social contract – let alone concern as to its frailty – my eyes lit up! In particular, the frailty the FT points to is traced directly to the perverted one-way nature of today’s social contract. The FT notes that few seem to benefit, while many see little to gain despite their abidance to the ‘rules of the game’ implied by the unwritten contract.

It may sound academic, but the concept of a social contract is not new. Western philosophers in the 17th and 18th centuries – like Thomas Hobbes, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and John Locke – made major contributions acknowledging the nature of the contract, or bargain, being made.

There would be a curtailment of individual rights (for example, the obligation to pay taxes) in exchange for the cloak of collective security and defence provided by the collective state. The right to private property to be protected by the state in exchange for agreed rules (and payment of taxes) as to the boundaries for business and other practices.

Over time the nuances of the contract varied, with differing versions emphasising specific rights above others. Undoubtedly, the powers of the status quo drove the development of the contract highlighting the rights (as opposed to responsibilities) of property owners. Nevertheless, this implicit agreement continues to provide the foundation for orderly commerce, economy, society, and government today.

However, the idea of a community reliant on each other, each with obligations and responsibilities, would not be new for many indigenous societies. Indeed, such ideas pre-dated the above western philosophers. The originating perspective in pre-colonial indigenous societies may have been different, perhaps tending towards a collective perspective on responsibilities and property rather than towards individualistic perspective on rights.

Unarguably, though, the impact of colonisation perverted the perspective of the social contract, towards emphasising individual rights rather than obligations to each other.

A radical new deal?

But what now? What might a social contract for 21st century Aotearoa look like?

The sub-header in the FT editorial Radical reforms are required to forge a society that will work for all is telling. Also telling is the following quote:

Radical reforms — reversing the prevailing policy direction of the last four decades — will need to be put on the table. Governments will have to accept a more active role in the economy. They must see public services as investments rather than liabilities, and look for ways to make labour markets less insecure. Redistribution will again be on the agenda; the privileges of the elderly and wealthy in question. Policies until recently considered eccentric, such as basic income and wealth taxes, will have to be in the mix.

The radical reforms posited by the FT might seem a dream for now, but a frail contract will only be worthy of resurrection if the perversions of the current contract are radically replaced.

In an earlier life, I toyed with the social contract space while on the Welfare Expert Advisory Group. During discussions about sanctions to enforce beneficiary obligations to find paid employment, there was an exploration of the balancing obligations of the state (or the community). If people were obliged to find jobs, was there not a balancing obligation on someone(?) to ensure such jobs were worthwhile? This was reflected – ever so politely – in Recommendation 10 (chapter 6) of Whakamana Tangata, and the related commentary.

The current obligations and sanctions regime must be immediately reformed into a system of mutual expectations and responsibilities … The overarching expectation of welfare recipients and MSD is to act with respect and integrity in their mutual interactions.

Later, the Productivity Commission report Fair Chance for All (chapter 4) discussed a social floor – or a baseline standard of living – in the context of a social contract.

… there has been a view that economic activity must also acknowledge the implicit constraints on activity arising from the need to ensure community or social acceptance of such activity.

During my contributions to these discussions I was driven by the concept of reciprocity and care – or tauututu alongside manaakitanga. If we are to look after each other, then encouraging someone to do something must include an offer of something in return. And that something must be of worth (value) to them. Rather than sanctions forcing people to do things, perhaps providing genuine rewards for such activity may be more successful2.

With this context, and welcoming the FT’s permission to explore radical reforms, I propose and forward (below) my version of the new social contract for Aotearoa 2025 and beyond.

This contract is not to designed to extract a favourable bargain for any party. On the contrary, it is designed to emphasise the connections between all parties and their respective reliance on each other fulfilling their respective obligations. Consequently, particular aspects of the contract should not be read in isolation to others. Further, a party cherry-picking items of their interest alone would be counter-productive. It is the package together that would build a prosperous Aotearoa for the 21st century.

The objective is a mutually reinforcing system where we all have reciprocal expectations as to obligations, entitlements, rights, and responsibilities.

Social Contract for Aotearoa 2025

Preamble

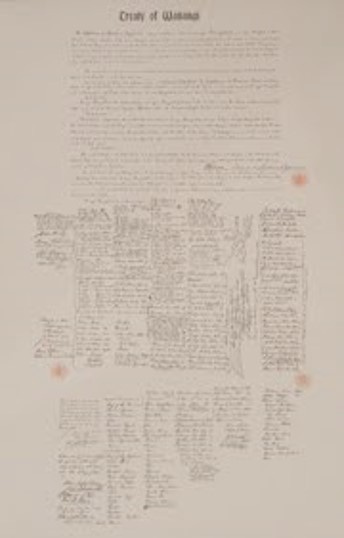

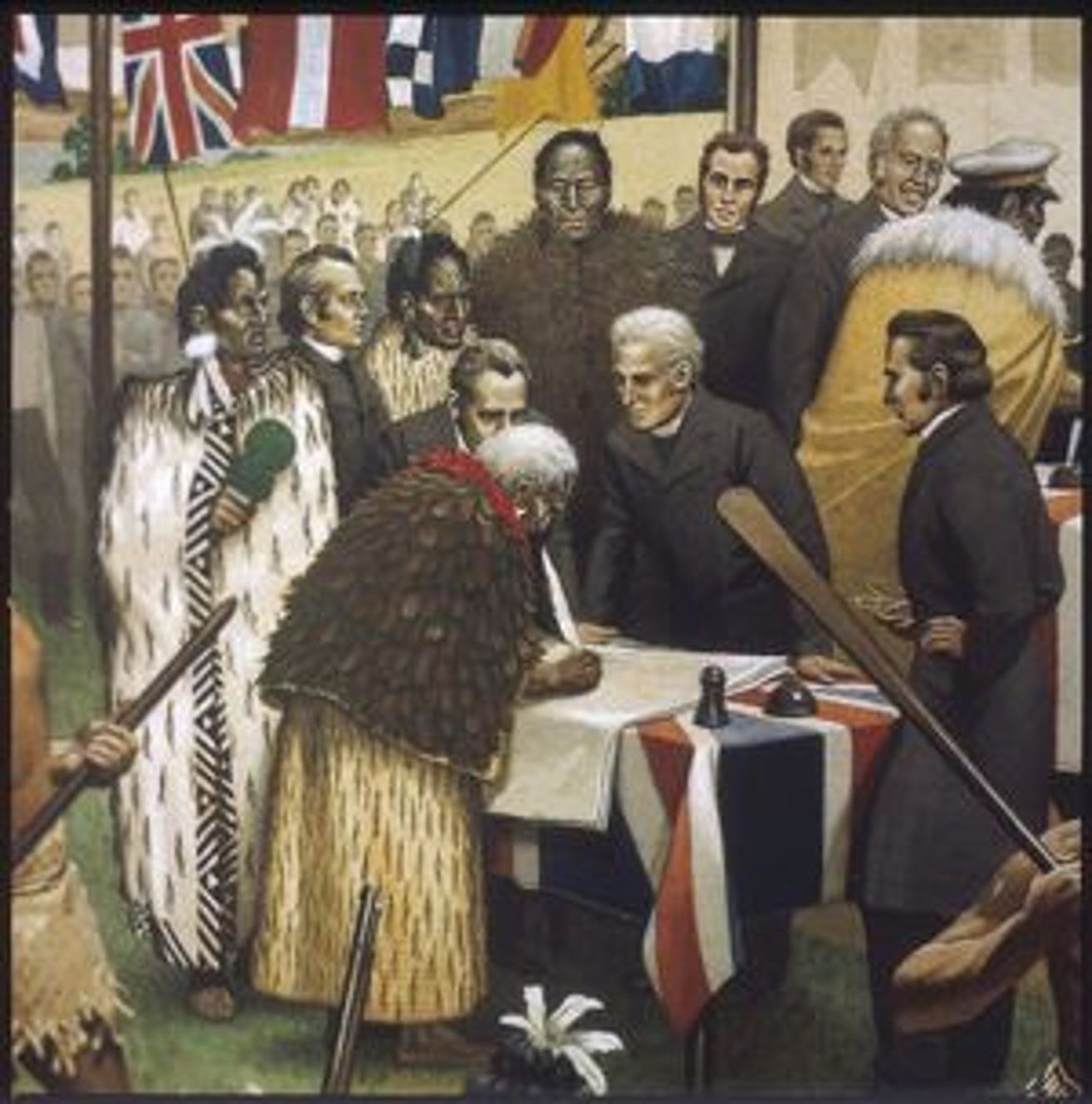

Te Tiriti o Waitangi foundations frame this Social Contract, with economic pillars placed upon this foundation.

The relationships between each of the parties to this Social Contract are reflected by their respective responsibilities and/or obligations in relation to each of Te Tiriti foundations and economic pillars.

In relation to each of the foundations and pillars, at least one party has expected entitlements or rights. These are balanced by the expected obligations or responsibilities of at least one party. Some of the foundations and pillars are listed as requiring an explicit implementation agent role for government.

There are seven parties to this Social Contract. Some people, organisations, and institutions will identify with more than one of these parties. In such instances it is important to be clear which ‘hat’ is being worn when interpreting expected obligations, entitlements, rights, and responsibilities. For example, the obligations of an individual need to be seen alongside the obligations of community (of which an individual is a member). Further, the responsibilities of an individual may also need to be seen alongside the responsibilities of iwi/Māori, while an individual in business may also need to view the responsibilities of business.

A broad perspective of community is adopted. For practical purposes the vehicles of participatory democracy and representative councils alongside a representative parliament could be structured to undertake the responsibilities and enjoy the entitlements of the community. Similarly, a broad definition of business is also adopted, capturing organisations, enterprises, corporates, not-for-profits, and other institutions engaged in any economic activity. In addition, government is viewed here as primarily an implementation vehicle with governance authority – akin to an executive or Cabinet function. In such a world a much clearer distinction between the roles and personnel of a parliament (responsible and accountable to community) and Cabinet (responsible for implementation) is envisaged.

It should be noted that both future generations and Papatūānuku are also listed as two explicitly named parties to this Social Contract. For practical purposes, each of their obligations and responsibilities would need to be acknowledged at any (and all) decision-making tables.

Commentary

Te Tiriti o Waitangi foundations for this Social Contract are reflected in the strategic direction for the country being set and driven by expectations of community, iwi/Māori. Additionally, the voices of future generations and Papatūānuku have an explicit role to play in setting the long-term strategic direction of the nation. Government is seen as responsible for the implementation of the long-term strategic direction for the country.

Governance authority is received by government from iwi/Māori and community. Te Tiriti foundations ensure the nature and limits of this authority are mutually agreed by iwi/Māori and government, in line with Te Tiriti. In particular, it is recognised that rangatiratanga for iwi/Māori is retained by iwi/Māori. Additionally, specific equity obligations on government, in line with Article 3 of Te Tiriti, are explicitly recorded.

The economic pillars begin by specifying sustainable relationship obligations to Papatūānuku on all parties, alongside the entitlement of all parties to enjoy life-sustaining environments and eco-systems delivered by Papatūānuku.

Reflecting Tino Rangatiratanga, explicit mana-enhancing opportunities for iwi/Māori see obligation for delivery, and entitlement to access, both lying with iwi/Māori.

The boundaries for acceptable economic activity, behaviour and actions are captured in a combination of pillars describing a licence to operate, rules of behaviour, and guidance as to tikanga of mana whenua. A licence to operate is provided to business by individuals, community, and iwi/Māori. Rules of behaviour are provided to individuals by community. Tikanga guidance is provided to individuals, business, community, and iwi/Māori by iwi/Māori. Detailed components of each of these pillars undoubtedly require discussion before agreement, but should at the high level reflect the shared values, ethics, and moral compass of the nation and its aspirations.

A social floor is guaranteed for individuals by community. Similarly, the detailed components of the social floor would require considerable discussion before agreement; although I would proffer the following as a starting point

adequate income for all

rights to food, shelter, and energy

genuine opportunities to participate and contribute

access to education, training, and health services

In mutual exchange for this guarantee is a responsibility on individuals to participate and contribute to community – whether through unpaid caring, volunteering, learning and training, and/or paid employment activities. Further, iwi/Māori are entitled to expect whānau and hapū to be connected and active in the community.

This Social Contract sees government as responsible for formalising and implementing the social floor, the rules of behaviour and the licence to operate. Where necessary, the implementation role may also require adjudication and enforcement activities.

Business have an expected entitlement to a skilled workforce, and the obligation is on individuals and community to provide such a workforce. In mutual exchange individuals have an entitlement to good jobs with rewarding incomes, with the obligation on business to deliver such good jobs.

In mutual exchange for being members of the community – and enjoying the rights, and entitlements that such membership brings – individuals and business are obliged to deliver membership fees (in the form of taxes, levies, rates, and duties) to government.

The following sections of this Social Contract list

parties

foundation and pillars

expectations of obligations, entitlements, rights, and responsibilities of each party

Parties

individuals

community

iwi/Māori

government

business

future generations

Papatūānuku

Foundations and pillars

Te Tiriti o Waitangi foundation

long-term strategic direction for nation

set by community, iwi/Māori, future generations, and Papatūānuku

responsibility for implementation by government

enjoyed by individuals, community, iwi/Māori, business, future generations, and Papatūānuku

governance authority

given by iwi/Māori and community

received by government

mutually agreed relationship recognising Tino Rangatiratanga and the nature and limits of governance authority for all, in line with Te Tiriti o Waitangi

mutually given by iwi/Māori and government

mutually received by iwi/Māori and government

resources, services, and programs ensuring equitable outcomes for Māori in line with Article 3 of Te Tiriti o Waitangi

delivered by government

received, accessed, and enjoyed by iwi/Māori

Economic pillars

mutually sustainable and respectful relationships and activities for all

given and delivered by individuals, business, community, iwi/Māori, government, and future generations

received and enjoyed by Papatūānuku

life-sustaining environment and eco-systems

given and delivered by Papatūānuku

received and enjoyed by individuals, business, community, iwi/Māori, government, and future generations

development of equitable mana-enhancing opportunities for Māori to reach their potential

delivered by iwi/Māori

received, accessed, and enjoyed by iwi/Māori

licence to operate in a cohesive community, recognising well-respected and enforceable contracts to trade

given, set, and delivered by individuals, community and iwi/Māori

responsibility for implementation by government

received, accessed, and enjoyed by business

rules of behaviour reflecting the values, ethics, and moral compass of community

given, set, and delivered by community

responsibility for implementation by government

received and enjoyed by individuals

tikanga guidance of mana whenua to enable thriving whānau and hapū

given, set, and delivered by iwi/Māori

received, accessed, and enjoyed by individuals, business, community, and iwi/Māori

social floor encompassing: adequate income for all; rights to food, shelter, and energy; genuine opportunities to participate and contribute; and access to education, training, and health services

given, set, and delivered by community

responsibility for implementation by government

received, accessed, and enjoyed by individuals

meaningful participation and contribution in community through at least one of a range of activities across unpaid caring, volunteering, learning and training and/or paid employment

given and delivered by individuals

received, accessed, and enjoyed by community

connected whānau and hapū active in their communities

delivered by community

received, accessed, and enjoyed by iwi/Māori

skilled, trained, innovative, and highly productive workforce

given and delivered by individuals and community

received, accessed, and enjoyed by business

good jobs providing appropriately rewarding incomes and mana-enhancing opportunities for individuals to reach their potential

given and delivered by business

received, accessed, and enjoyed by individuals

community membership fees (taxes, levies, rates, and duties)

given and delivered by individuals and business

received and accessed by government

Obligations, responsibilities, entitlements, and rights of each party

Individuals

Entitlements and/or rights to receive, to access, and/or to enjoy

life-sustaining environment and eco-systems

rules of behaviour reflecting the values, ethics, and moral compass of community

tikanga guidance of mana whenua to enable thriving whānau and hapū

social floor encompassing

adequate income for all

rights to food, shelter, and energy

genuine opportunities to participate and contribute

access to education, training, and health services

good jobs providing appropriately rewarding incomes and mana-enhancing opportunities for individuals to reach their potential

Obligations and/or responsibilities to give, to set, and/or to deliver

mutually sustainable and respectful relationships and activities for all

a licence to operate in a cohesive community, recognising well-respected and enforceable contracts to trade

meaningful participation and contribution in community through at least one of

unpaid caring

volunteering

learning and training

paid employment

skilled, trained, innovative, and highly productive workforce

community membership fees (taxes, levies, rates, and duties)

Community

Entitlements and/or rights to receive, to access, and/or to enjoy

life-sustaining environment and eco-systems

tikanga guidance of mana whenua to enable thriving whānau and hapū

meaningful participation and contribution in community through at least one of

unpaid caring

volunteering

learning and training

paid employment

Obligations and/or responsibilities to give, to set, and/or to deliver

long-term strategic direction for nation

governance authority

mutually sustainable and respectful relationships and activities for all

licence to operate in a cohesive community, recognising well-respected and enforceable contracts to trade

rules of behaviour reflecting the values, ethics, and moral compass of community

social floor encompassing

adequate income for all

rights to food, shelter, and energy

genuine opportunities to participate and contribute

access to education, training, and health services

connected whānau and hapū active in their communities

skilled, trained, innovative, and highly productive workforce

Iwi/Māori

Entitlements and/or rights to receive, to access, and/or to enjoy

mutually agreed relationship with Government recognising Tino Rangatiratanga and the nature and limits of governance authority for all, in line with Te Tiriti o Waitangi

resources, services, and programs ensuring equitable outcomes for Māori in line with Article 3 of Te Tiriti o Waitangi

life-sustaining environment and eco-systems

development of equitable mana-enhancing opportunities for Māori to reach their potential

tikanga guidance of mana whenua to enable thriving whānau and hapū

connected whānau and hapū active within their communities

Obligations and/or responsibilities to give, to set, and/or to deliver

long-term strategic direction for nation

mutually agreed relationship with Government recognising Tino Rangatiratanga and the nature and limits of governance authority for all, in line with Te Tiriti o Waitangi

mutually sustainable and respectful relationships and activities for all

development of equitable mana-enhancing opportunities for Māori to reach their potential

licence to operate in a cohesive community, recognising well-respected and enforceable contracts to trade

tikanga guidance of mana whenua to enable thriving whānau and hapū

Government

Entitlements and/or rights to receive, to access, and/or to enjoy

governance authority

mutually agreed relationship with iwi/Māori recognising Tino Rangatiratanga and the nature and limits of governance authority for all, in line with Te Tiriti o Waitangi

community membership fees (taxes, levies, rates, and duties)

Obligations and/or responsibilities to give, to set, and/or to deliver

mutually agreed relationship with iwi/Māori recognising Tino Rangatiratanga and the nature and limits of governance authority for all, in line with Te Tiriti o Waitangi

resources, services, and programs ensuring equitable outcomes for Māori in line with Article 3 of Te Tiriti o Waitangi

mutually sustainable and respectful relationships and activities for all

Obligations and responsibilities for implementation

(including formalising, communicating, monitoring, promoting, adjudicating, and enforcing)

long-term strategic direction for nation

licence to operate in a cohesive community, recognising well-respected and enforceable contracts to trade

rules of behaviour reflecting the values, ethics, and moral compass of community

social floor encompassing

adequate income for all

rights to food, shelter, and energy

genuine opportunities to participate and contribute

guaranteed access to education, training, and health services

Business

Entitlements and/or rights to receive, to access, and/or to enjoy

life-sustaining environment and eco-systems

licence to operate in a cohesive community, recognising well-respected and enforceable contracts to trade

tikanga guidance of mana whenua to enable thriving whānau and hapū

skilled, trained, innovative, and highly productive workforce

Obligations and/or responsibilities to give, to set, and/or to deliver

mutually sustainable and respectful relationships and activities for all

good jobs providing appropriately rewarding incomes and mana-enhancing opportunities for individuals to reach their potential

community membership fees (taxes, levies, rates, and duties)

Future generations

Entitlements and/or rights to receive, to access, and/or to enjoy

long-term strategic direction for nation

life-sustaining environment and eco-systems

Obligations and/or responsibilities to give, to set, and/or to deliver

long-term strategic direction for nation

mutually sustainable and respectful relationships and activities for all

Papatūānuku

Entitlements and/or rights to receive, to access, and/or to enjoy

long-term strategic direction for nation

mutually sustainable and respectful relationships and activities for all

Obligations and/or responsibilities to give, to set, and/or to deliver

long-term strategic direction for nation

life-sustaining environment and eco-systems

Of course, the accompanying narrative ignores the fact that beneficiaries do indeed pay tax (it’s called GST). It is the promotion of an us v them view of the world that the status quo powers wish to exploit, irrespective of inconvenient facts.

Not to mention reduced enforcement activity being required, and so lower associated costs.