Alex's employment pays $6.07 per hour

The non-simple, non-sense world of WFF (=FTC+IWTC), JS, WEP, ASUP, together with PAYE and ACC, leading to the EMTR chokehold.

Meet Alex and Taylor and their 2 children. Alex could work for 40 hours a week, bringing in an additional $6.07 per hour in the hand, for the family.

If Alex doesn’t accept this somewhat derisory offer of employment, both Alex and Taylor stand accused of being lazy layabouts, a burden on “the taxpayer”, and irresponsible parents, while also risk being sanctioned by Work and Income for not taking up the employment that is available.

The picture below summarises the situation of Taylor and Alex’s family income. Their family income comes from wages from Taylor’s full-time employment plus a range of assistance payments, depending on the number of weekly hours of paid employment Alex agrees to take up.

Relevant facts their story include

Taylor is employed full-time at $25 per hour, which brings in $1,000 gross a week or $52,000 per year

Deductions for income tax and ACC levies bring these figures down to a weekly $829.30 (or an annual $43,124) in the hand.

Taylor and Alex rent a 2 bedroom house in Island Bay, paying the median rent for the suburb1 of $625 per week.

Nothing too complicated yet.

Of course, $829.30 in the hand is impossible to live on as it leaves just $204.30 per week for all other non-rent living costs and expenses. So, yes, there are assistance payments available to help the family out with their budgeting challenges.

But, this is where things get complicated - so please hold on tight.

Neither simple nor sensible

For assistance, Alex can apply for Jobseeker Support (JS) payments while also seeking some part-time work. In addition, there is Working For Families (WFF) assistance, comprising Family Tax Credit (FTC) and In-Work Tax Credit (IWTC) available2. There is also Accommodation Supplement (ASUP) assistance to this family.

The complications arise because calculating the amount of any of these other assistance payments are neither simple nor sensible. They are non-simple because each of the amounts are dependent on how much is earned and how much is paid in each of the other categories of assistance. And the nightmare inter-dependencies, creating the picture above, illustrates the non-sense illustrated by the black dotted line. This line is known by economists and policy experts alike as the Effective Marginal Tax Rate (EMTR).

An early spoiler alert, the EMTR beast is truly the villain in the story of Taylor and Alex and their family.

The beginning

Let’s go back to the start, where Taylor is employed full-time and Alex is not in employment but receives weekly JS of $324.61 in the hand. Eligibility for the FTC and ASUP adds another $114.21 and $213.50, respectively, to the family’s weekly income in the hand.

Note, both of these assistance payments are already reduced from the maximum possible for these supplements because of the other income3 the family receives. As Alex gets JS they also qualify for the WEP4, which adds another $13.37 per week. In total, they end up with $1,494.99 in the hand each week (or an annual $77,739). Not quite, but in the region of in the hand income for the mythical average household5.

Nevertheless, with a post-rental in the hand of $869.99 per week, Taylor and Alex continue to face some challenging budgeting decisions to meet the food, power, clothing, transport, personal care and hygiene and other costs for them and their 2 children each week6.

Sadly, their decisions from here do not get any easier. But please stay with me, as their story must be told.

Working to ease their budget challenge

One big hurdle is that Alex’s application for JS comes with strings attached. One of those strings is an expectation to search for and accept employment offers. In addition, there may be training obligations or attendance at work-ready courses.

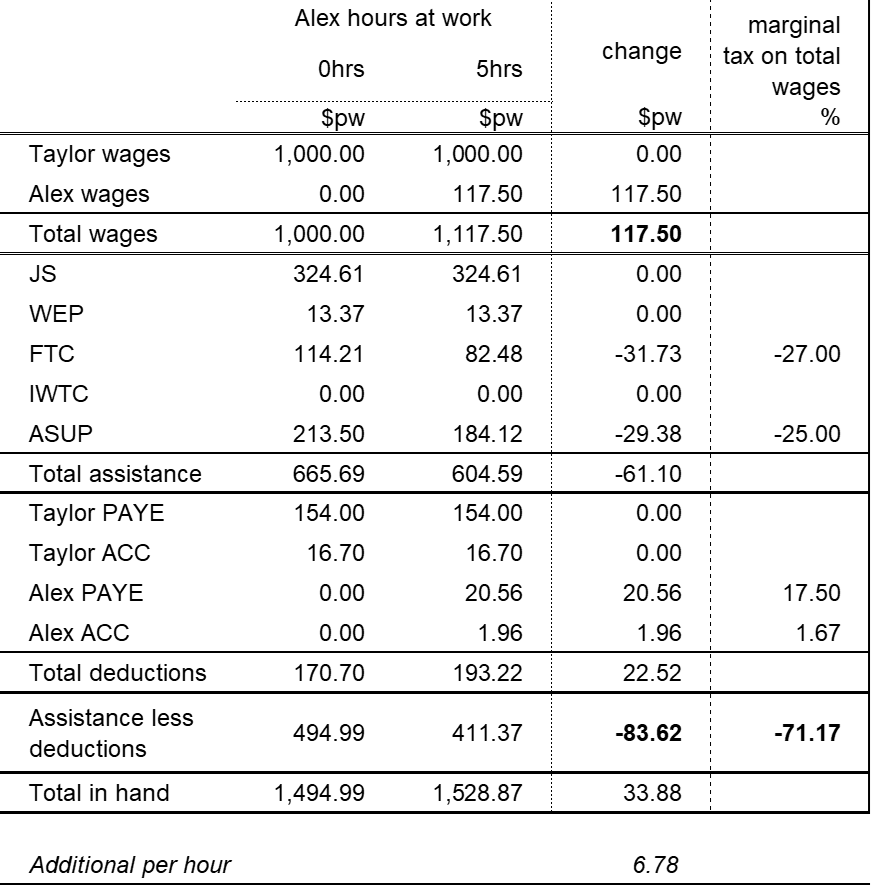

In the first instance, Alex signs up for 5 hours at the local supermarket over the weekends, so there is no need to arrange childcare given Taylor’s weekday work hours. Alex knows that 5 hours at the minimum wage of $23.50 per hour will not effect the JS payment, as it brings in less than the threshold $160 per week. The family looks forward to a few more dollars in the hand to ease their budget challenges.

However, while JS payments stay at the $324.61 level, the additional income from Alex’s 5 hours a week means the family’s FTC and ASUP payments decline considerably7. As a result, Alex’s extra 5 hours provides the family an extra $33.88 in the hand, with their weekly total now amounting to $1,528,87.

$33.88 extra in the hand from $117.50 of wages effectively implies a ‘tax’ of $83.62.

$83.62 on $117.50 means an EMTR of 71.2%.

That is, an extra $33.88 for 5 hours of work.

The arithmetic may be obtuse for some, but I’d be pretty clear in believing that $6.78 an hour would be fairly unattractive to most.

Aspiring to escape the chokehold

But it gets even messier; please stay with me.

Taylor and Alex have never shied from obligations to contribute, while also remembering the prospect of MSD sanctions would not assist in alleviating any financial or other stresses faced by the family. Additionally, like many of their peers, they aspire to home ownership, and do recognise the need to save to build a retirement nest egg. While these hopes seem distant, Alex and Taylor retain their sense of hope. And so they explore options for Alex to shift to 10 hours a week.

Sadly, it does not brighten the story. At 10 hours a week, Alex brings in more than the $160 per week threshold. Jargon aside, this means additional income starts impacting on the level of JS payment being received.

In particular, each additional dollar above $160 per week reduces the JS payment by a gut-punching 70 cents. Deducting the further losses of FTC and ASUP payments results in the family total in the hand rising by just $14.47 to $1,543.33.

Increasing Alex’s part-time work from 5 to 10 hours a week gets Taylor and Alex another $14.47 for the family.

Yup, that’s under $3 for each extra hour of work.

Look closely at the chart and you will see the blue bars beginning to decline, as do the orange and grey bars. And the black dotted line soars from a punishing 71.2% EMTR to a stratospheric 97%, as Alex and Taylor are effectively caught on a treadmill running to stand still8.

And, don’t forget the threat of sanctions - ie. even lower JS payments - continues to hover over the heads. Further, the 10 hours a week needs to be squeezed into weekends and evening shifts to avoid childcare costs. I will leave those with more relevant expertise to comment as to what this ‘choice’ does to quality family time, but I would be surprised if it was positive.

The treadmill eases up, but the non-sense remains

Working even more employment hours, continues to be non-simple and adds further non-sense to the story.

As Alex’s employment rises to more than 10 hours a week, the JS and WEP are eliminated, but are effectively replaced by higher FTC payments, alongside eligibility for IWTC payments. Consequently, the incredibly punitive EMTR of over 95% gradually returns to the lower, but still punitively high, rate of 71.2%9. The simplicity and sense of any of these changes in payments remains mysterious to many.

Moving to 15 or more hours a week, this punitively high 71.2% EMTR is locked in, with wage income gradually replacing the assistance payments. As illustrated, ASUP payments continue to erode, as do the accompanying FTC and IWTC assistance payments. Consequently, the in the hand total available to the family does indeed creep upwards, but at a seemingly slow snail’s pace.

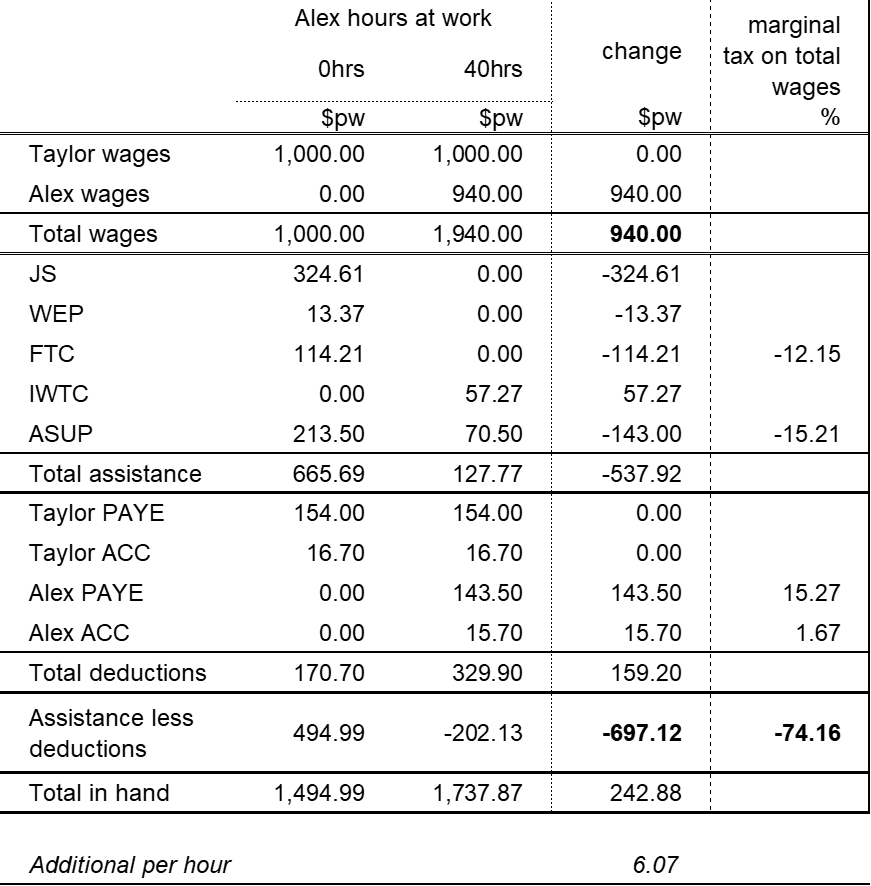

The finale

The finale of this story sees Alex in full-time 40 hours a week paid employment at the minimum wage. The family finishes with $1,737.87 in the hand each week, up $242.88 from the $1,494.99 the family had when Alex was not in any paid employment but was at the whim of the benefit police and the risk of associated sanctions.

Yes, a $242.88 lift in the hand for the family budget sounds attractive.

But the arithmetic shows a return of $6.07 per hour for 40 hours of paid employment.

According to the MBIE tenancy bond database.

As both children are older than 3 years, the family is ineligible for Best Start payments. Also, I use the term family throughout, although household may be more correct for official terminology when assessing eligibility criteria. The distinction is important for some elements, but not relevant in Taylor and Alex’s case where family seems the more appropriate term.

For the purposes of FTC and ASUP, other family income includes JS payments.

The WEP is only paid in the winter months, but for ease of calculation this story assumes it is paid out evenly across the year.

Statistics New Zealand Tatauranga Aotearoa Household Economic Survey (Income) estimates median household disposable income for the year ended June 2024 (latest data) as $86,257.

Statistics New Zealand Tatauranga Aotearoa Household Economic Survey estimates average household weekly expenditure for the year ended June 2023 (latest data) as $1,597.50, or an annual $83,070. For non-housing expenditure, the estimate is $1,252.30 per week.

Payments decline by what is officially known as the abatement rate - which is 27 cents for FTC payments and 25 cents for ASUP payments, for each additional $ of family income. Family income in this context includes JS payments.

I know that whataboutism does not in general contribute to robust argument, I can not resist pointing to some who claim a top tax rate of 39 cents is a ‘disincentive’ to work. I wonder what those same people would think of tax rates of 71.2 cents, or 97 cents.

The abatement rate for IWTC is also 27 cents for each additional $ of family income.