Solemn, compelling, and overwhelming case to discard RSB in its entirety

Submission to Finance and Expenditure Committee

My submission to the Finance and Expenditure Committee on the Regulatory Standards Bill is reprinted below.

Personal details

This submission is from Dr Ganesh Rajaram Ahirao (aka Dr Ganesh Nana).

I recognise Māori as Tangata Whenua of Aotearoa. I am Tangata Tiriti, a first-generation New Zealander born in Te Awakairangi (Lower Hutt) and raised in Te Awakairangi ki Uta (Upper Hutt) to parents who emigrated from India in the 1950s as young newly-weds.

I have a PhD in economics from Victoria University of Wellington Te Herenga Waka and have more than 40 years of experience and accumulated knowledge with a professional career in economics that has included academia, consulting, and public service.

More recently, I was Chair of the Independent Crown Entity the Productivity Commission Te Kōmihana Whai Hua o Aotearoa from February 2021 until its disestablishment in February 2024.

I wish to appear before the Committee to speak to my submission.

I can be contacted at ganesh.r.ahirao@gmail.com.

Submission

I oppose the Regulatory Standards Bill.

There are two parts to my opposition. The first part relates to the breach – and potential further breaches – of te Tiriti o Waitangi, as conveyed in the reported findings of the Waitangi Tribunal. The second part relates to the economic framework and assumptions that underpin the Bill and, in particular, clause 8 stating the Principles of responsible regulation.

In summary, the Bill being considered by this Committee

has involved breaches by the Crown of te Tiriti principles of partnership and active protection, as found by the Waitangi Tribunal

by failing to meaningfully consult with Māori before Cabinet took significant decisions as to the content of the proposed Regulatory Standards Bill on 5 May 2025

by introducing the proposed Regulatory Standards Bill to the House without such meaningful consultation

and risks further breaches if the Crown proceeds to enact the Regulatory Standards Act without consulting meaningfully with Māori.

imposes an economic framework underpinned by a narrow worldview of interests, property, and rights that

asserts the primacy of the individual, in line with a narrow 17th century view of a uni-directional social contract

assumes the current distribution of interests, property, and rights (and, by implication, financial income and wealth) is Pareto optimal; and, by omission, ignores the method and/or transactions through which such property and rights have been previously acquired

implicitly assumes no externalities in that there are no responsibilities or obligations on those who possess interests, property and exercise rights.

Comments

I comment in relation to each of the two parts forming my opposition to the Regulatory Standards Bill (the Bill), followed by some concluding comments.

Part I: Breaches of, and potential further breaches of, te Tiriti o Waitangi

Toitū Te Tiriti o Waitangi

As Tangata Tiriti I am proud to stand alongside Tangata Whenua in the assertion of Tiriti rights, expectations, and obligations.

I note the findings and recommendations of the Waitangi Tribunal contained in its Interim Urgent report[1]. I acknowledge, respect, and humbly defer to the superior wisdom and experience of the Tribunal in Tiriti matters.

I strongly urge and encourage members of this Committee to heed their findings and recommendations.

Part 2: Economic framework underpinned by narrow worldview

This Bill focusses on interests, liberties, laws, property, taxes, fees, levies and the role of courts. The protection of such interests, liberties, laws, property, and the role of courts, alongside the levying of taxes, fees, and levies, enables economic activity to be pursued.

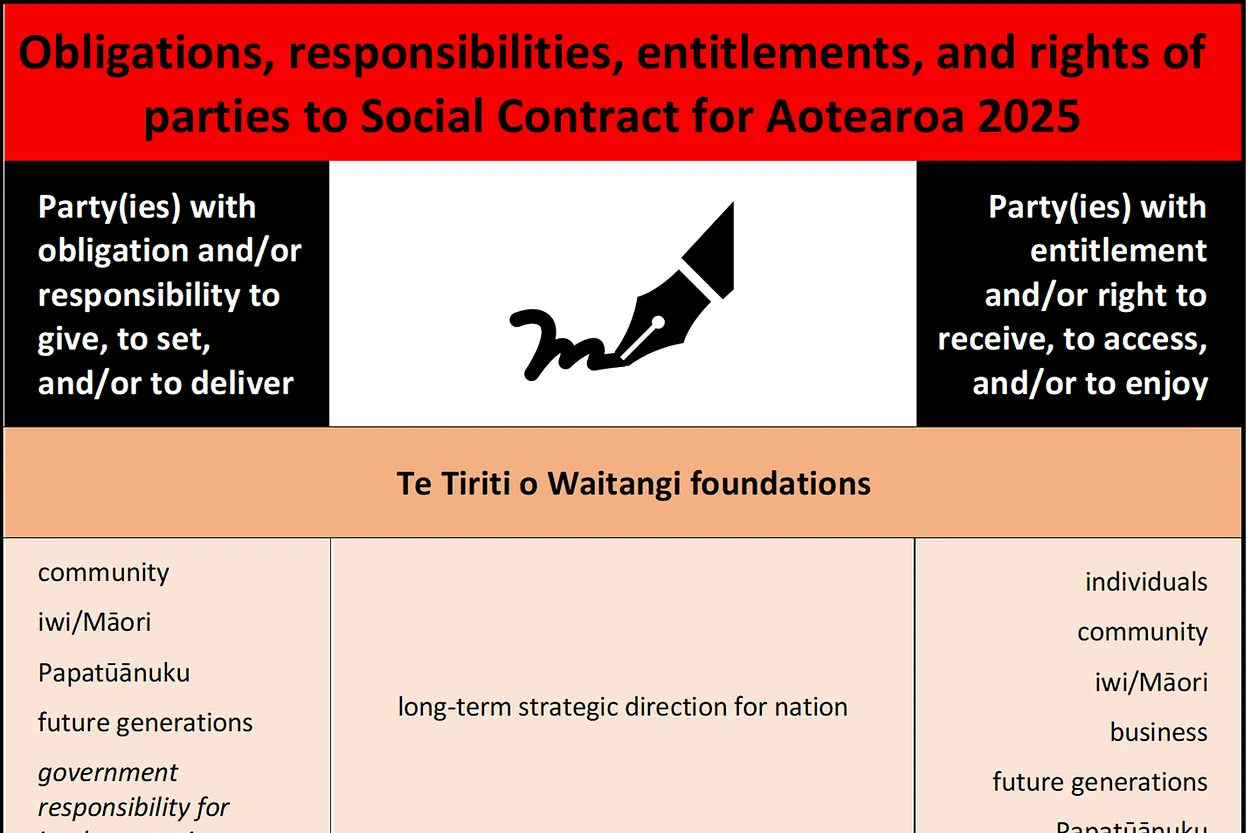

However, the Bill adopts an essentially 17th century view of a social contract almost exclusively between individuals and government. Such a view posits a uni-directional social contract restricted to individuals with interests and property who accept limitations on their rights in exchange for obligations on government to protect their interests and property

It is underpinned by a narrow, silo-oriented view of economic activity, which is perpetuated – in particular – by the principles of responsible regulation stated in clause 8. The protection of existing rights and interests is implicitly the objective, as none other is presented. In turn, this protection supports the promotion of continued economic activity based on these rights and interests, as per a 17th century view of a social contract.

While the listed characteristics may pass the test of being principles of regulation, the test of the principles being responsible is simply conjecture as little evidence is presented to support the assertion. Thus, the logic leads to the conclusion that regulation that protects existing rights and interests is a goal in and of itself.

The circularity in argument is breathtaking.

For the description of responsible to be informative, there needs to be an explicit objective against which the exercise of responsibility can be assessed. A social contract more relevant to the 21st century would suggest an objective aligned to the overarching goal of government – one that requires the protection and promotion of the interests, liberties and properties of all.

The clause 8 principles of responsible regulation omit, or ignore, any overarching objective against which the exercise of such responsibility can be assessed. Rather it adopts a narrow framework that asserts the primacy of the individual, ignores the inherent sub-optimality of the starting point, and assumes no externalities result from the economic activity and transactions that are undertaken.

Primacy of individuals

The underpinning approach of the Bill accepts a narrow version of a social contract, which focusses almost exclusively on the uni-directional relationship between individuals and government.

Of most significance in establishing a social contract relevant to Aotearoa in the 21st century[2] is to encompass iwi/Māori, collective/community, as well as future generations as parties to that understanding. The uni-directional nature would also need to be replaced by recognising expectations, rights, obligations and responsibilities of all parties. Further, recognising the respective interests and rights of maunga and awa with personhood status would likely be considered.

That individual private rights implicitly outweigh the rights of communities (for example, the right to adequate and accessible drinking water for all) makes this Bill particularly restrictive and worrisome. Similarly restrictive and worrisome is the implication that individual private rights outweigh the rights of future generations (for example, the right to mana-enhancing natural eco-systems sustainably delivering amenity value).

The societal norms of collectively- and community-owned assets and facilities are embraced by many in 21st century Aotearoa, alongside obligations and responsibilities to future generations. Giving primacy to individuals would severely hinder the regulation of economic activity in line with any widely-accepted social contract relevant for 21st century Aotearoa.

Ignores inherently sub-optimal starting point

There is a foundational assumption in the underpinning framework of this Bill. That is, the existing state of the world is assumed to be (in terms of distribution of property and wealth and, so, rights) Pareto optimal. Pareto optimality is seen by some as assured given unencumbered market transactions undertaken by rational economic actors.

Pareto optimality – in short – is a condition where any shift in the allocation of economic resources would not be able to lead to an improvement in someone’s (or groups’) welfare[3] while leaving no-one worse off. That is, in attempting to make someone better off (given a Pareto optimal starting point), you will always be making at least one other person worse off. Such a Pareto optimal situation is sometimes asserted as "efficient" and/or "preferred" and/or “fair”[4]. Hence, it is argued that the status quo allocation of resources is preferred.

However, Pareto optimality must be called into question when recognising the power imbalances present (and, arguably, still present) at the time transactions took place. The condition for unencumbered market transactions undertaken by rational economic actors was clearly not satisfied for many historical exchanges. Consequently, it is highly tenuous to claim the resulting allocation of economic resources, and consequential current distribution of wealth, property, interests, and rights as being Pareto optimal.

Further, claiming (or assuming) the current situation as being Pareto optimal clearly requires normative (value-laden) assessments of the worth of the welfare-enhancing improvements of some, at the expense of the welfare-reducing changes of others. The normative assessments that underlie such an assumption should be opened to critique before being agreed, or not, as valid and reflecting societal values and future aspirations.

Irrespective of normative assessments, the implicit assumption of an existing Pareto optimal situation remains a critical assumption. Pareto optimality depends critically on agreement as to the concept and characteristics of welfare-enhancing and welfare-reducing changes. Such an agreement would underpin and motivate the objective of economic activity as being the pursuit of welfare improvements. However, such an objective – as consistent with a 21st century version of a social contract – would likely include community/collective values and/or material and non-material outcomes. A shift from a 17th century narrow version of a world to a more relevant 21st century version of a world makes it difficult to hold this foundational assumption[5] as being valid.

Furthermore, the inclusion of the interests and rights of future generations (and the responsibilities and obligations to them of the current generation) in terms of the legacy they will inherit, again, indicates this assumption is not robust.

As alluded to earlier, the imbalances in power – including market power – in the current status quo situation need to be recognised. This Bill assumes this imbalance is irrelevant (or, by omission, ignores its presence outright) and proceeds to embed the primacy of existing interests and rights. This asserts – by implication – the preservation of the existing status is required for continued Pareto optimality.

Consequently, there is valid economic rationale to enable/encourage changes in terms of distribution of property and wealth and, so, rights. These changes need to ensure economic activity is directed to deliver on its social contract obligations to all – including the many communities, as well as future generations, that together make up Aotearoa. Such changes would be severely hindered by the enactment of this Bill.

No externalities

Similarly, underpinning this Bill is a worldview that no responsibilities or obligations are attached with the private property interests and rights that one possesses (or acquires). This is close to the economic assumption that there are no externalities to one's individual behaviour in the exercise of one’s rights. However, there are many examples of economic externalities, which is the very reason for regulations. In particular, there are many externality impacts on natural resources and eco-systems (for example, depleted waterways and threatened species) which in this worldview possess no rights or interests.

In the 21st century, rights and interests are rarely absolute. Some societal and community values embrace a "do no harm" obligation and responsibility on all members. This underpins many moral and ethical regulations that act to curtail the exercise of individual rights in undertaking economic activity. It is indeed telling that this obligation and responsibility is omitted from any of the principles in clause 8.

However, an assumption of no externalities is implicit in this Bill in its promotion of compensation being required for property interests and rights that may be curtailed. This is consistent with the total omission in the Bill of the responsibilities and obligations that are incumbent on those possessing private property and interests.

In overlooking the presence of externalities, this Bill would severely hinder attempts to limit harmful economic activity.

Parallel to section 26G of Public Finance Act

It is noted in the Explanatory Note to the Bill under the heading Purposes of Bill that the Bill “intends to bring the same discipline to regulatory management that New Zealand has for fiscal management”.

Sadly, that so-called discipline has not served many communities of Aotearoa well, leaving a legacy of neglected, dilapidated, and fragile natural resource systems, network connections, and social and physical infrastructure, with anaemic productivity outcomes alongside stressed and fractured communities.

Indeed, the framing of the principles of responsible fiscal management listed in section 26G of the Public Finance Act is eerily similar to that of the principles of responsible regulation listed in this Bill. Fiscal management, in line with section 26G, that satisfies fiscal goals – irrespective of consequential impacts – appears to be the objective of responsible fiscal management in and of itself. This is reinforced in the consequential sections 26J and 26K of that Act that specify long-term objectives and short-term intentions as relating directly to a set of fiscal variables.

Again, there is a set of principles of fiscal management that is unilaterally ascribed the description of responsible. There is no evidence presented to support the assertion that the principles are indeed responsible, as there is no external measure, barometer, or objective against which the exercise of responsibility can be assessed.

Yes, principles of fiscal management may be agreed around the trajectory for debt, operating balances, and net worth and the like. But what makes this management earn the title of responsible? Suggesting that achieving a set of fiscal objectives for the exercise of responsible fiscal management (without indicating what or why such actions could be described as responsible) involves breathtakingly circular logic, similar to that underlying the Bill this Committee is considering.

Such logic is akin to suggesting the measure of a responsible employer is an employer that provides employment. In such a case, many would rightly query against what criteria (beyond the provision of employment) makes this employer’s action able to be deemed responsible.

Concluding comment

This Bill is founded on an irrelevant 17th century view of a uni-directional social contract restricted to individuals with interests and property, who accept limitations on their rights in exchange for obligations on government to protect their interests and property.

Fast forward to 21st century Aotearoa, a relevant and widely-acceptable social contract would – in the least – include responsibilities and obligations on those with interests and property and also recognise interests and rights of non-individual economic actors. The development of a mutually-reinforcing set of rights, expectations, obligations, and responsibilities on all members of our communities (present and future) is necessary to ensure an equitable distribution of the benefits and costs of individual and collective activity.

This Bill claims to establish a set of principles that constitute responsible regulation. The set proposed is indeed a set of principles for the design of regulation. However, glaringly, there is no evidence that the stated set is responsible; for there is no criteria presented against which the responsibility (or otherwise) of the exercise of such principles can be assessed.

In addition, there are the findings of the Waitangi Tribunal indicating breaches and further potential breaches of Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

Consequently, there is a solemn, compelling, and overwhelming case that this Bill should be discarded in its entirety.

Recommendation

That this Bill be reported back to the House recommending that this Bill not proceed.

References

Ahirao G, Social contract needed to deliver a 'no BS' public health agenda, https://www.phcc.org.nz/briefing/social-contract-needed-deliver-no-bs-public-health-agenda, 30 May 2025

Ahirao G, What’s the deal? The social contract – a perversion awaiting radical reform, https://ganeshnana.substack.com/p/whats-the-deal?r=37e9m9, March 2025.

New Zealand Productivity Commission, A fair chance for all: Breaking the cycle of persistent disadvantage, June 2023.

Bagshaw P (et al), The common good: Reviving our social contract to improve healthcare. The New Zealand Medical Journal (Online), 138(1614), https://nzmj.org.nz/journal/vol-138-no-1614/the-common-good-reviving-our-social-contract-to-improve-healthcare, 2025

Waitangi Tribunal, Interim Regulatory Standards Bill Urgent Report Wai 3470, https://forms.justice.govt.nz/search/Documents/WT/wt_DOC_230792542/RS%20Bill%20W.pdf, 16 May 2025

[1] Interim Regulatory Standards Bill Urgent Report, Waitangi Tribunal (Wai 3470), https://forms.justice.govt.nz/search/Documents/WT/wt_DOC_230792542/RS%20Bill%20W.pdf, 16 May 2025.

[2] See, for example, discussions in New Zealand Productivity Commission (2023); Ahirao G (March and May 2025); and Bagshaw P et al (2025).

[3] In this context, welfare can be loosely seen as a synonym for economic utility, living standards, wellbeing, ora, or oranga.

[4] “Fair” in that the situation has resulted from the unencumbered market transactions undertaken by rational economic actors.

[5] The existing state of the world (in terms of distribution of interests, property and wealth and, so, rights) is Pareto optimal given the unencumbered market transactions undertaken by rational economic actors.